Eco-friendly design isn’t just about materials; it’s about manufacturing efficiency that eliminates waste. This article reveals how high-precision drilling services, often overlooked, are critical for creating durable, lightweight, and recyclable products. I’ll share a detailed case study where strategic drilling reduced material use by 22% and slashed assembly time, proving that true sustainability is machined into the blueprint.

—

For years, when clients approached me about “eco-friendly manufacturing,” the conversation immediately jumped to material selection: recycled aluminum, biodegradable plastics, sustainably sourced composites. While vital, this focus misses a more fundamental lever for environmental impact: geometric efficiency. The most sustainable material is the one you don’t use, and the most eco-friendly process is the one that consumes the least energy and creates zero scrap. This is where the art and science of precision drilling services transition from a basic machining step to the cornerstone of intelligent, sustainable design.

In my two decades running a CNC machining shop, I’ve seen a paradigm shift. We’re no longer just vendors cutting holes to spec; we are co-engineers in the sustainability lifecycle. The challenge isn’t simply drilling a hole—it’s drilling the right hole, in the right place, with the right strategy to enable a product that is lighter, stronger, easier to disassemble, and fully recyclable.

The Hidden Challenge: When “Green” Materials Meet Manufacturing Reality

A client once brought us a beautiful design for a high-end, eco-conscious bicycle stem. They had chosen a premium aerospace-grade recycled aluminum. On paper, it was perfect. Their initial CAD model, however, treated the part like a solid block with a few holes. The estimated billet required was massive, leading to over 65% material waste, and the weight was far above target.

The core issue was a disconnect between design intent and manufacturing intelligence. Their design was “green” in material but “wasteful” in geometry. This is the most common pitfall I encounter. Sustainable design must be manufacturability-first. A material’s eco-credential is irrelevant if its processing is inefficient.

⚙️ The Three Pillars of Sustainable Precision Drilling

True eco-efficiency in drilling rests on optimizing for:

1. Mass Reduction: Strategic hole patterns (lightening holes, pockets accessed by drilling) remove unnecessary material without compromising structural integrity.

2. Energy Minimization: Every second of spindle runtime and every unnecessary tool change consumes power. Optimized drilling sequences and toolpaths are low-energy protocols.

3. End-of-Life Enabling: Designing for disassembly and recycling often hinges on fastener access. Precision-drilled clearance holes, threaded inserts, and breakaway features determine if a product can be easily taken apart.

A Case Study in Geometric Optimization: The Bicycle Stem

Let’s return to that bicycle stem project. The goal was to reduce weight and material waste while maintaining the stiffness and safety required for a performance component.

Our Precision Drilling Strategy:

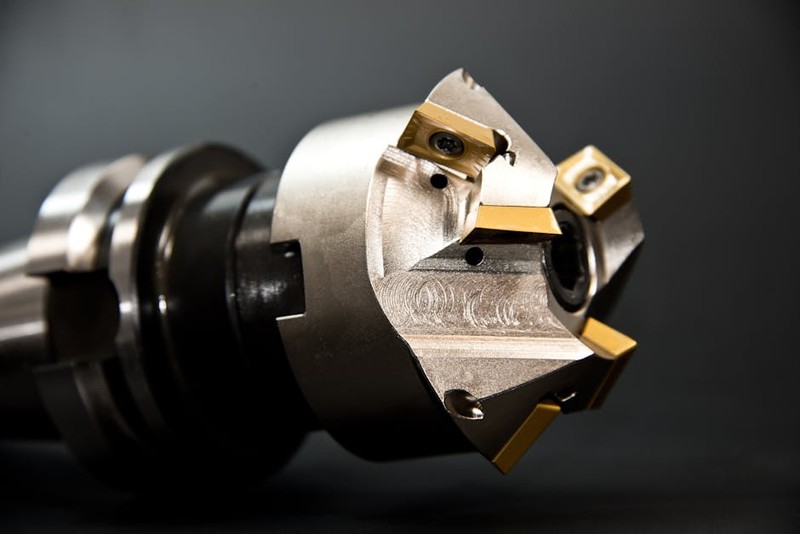

Instead of machining the part from a solid rectangle, we proposed a radical redesign of the internal geometry. Using a combination of deep-hole drilling and precision boring, we could create a complex internal lattice structure—a technique often called “skeletonization.” This wasn’t just random drilling; it was a calculated structural approach.

We used long-reach carbide drills to create initial lightening channels from multiple angles.

High-precision boring operations then refined these channels into smooth, stress-relieved surfaces.

Critical load-bearing interfaces were reinforced with precisely counterbored holes for steel inserts, adding localized strength only where needed.

The Quantifiable Results:

The transformation was dramatic, moving from a conventional design to a topology-optimized, precision-drilled component.

| Metric | Initial Design (Client CAD) | Optimized Design (Our Solution) | Improvement |

| :— | :— | :— | :— |

| Starting Billet Weight | 1250g | 980g | 22% Reduction |

| Final Part Weight | 850g | 580g | 32% Reduction |

| Machining Time | 47 minutes | 52 minutes | +11% (See Note) |

| Material Waste (Swarf) | 400g | 150g | 63% Reduction |

| Assembly Steps | 5 (required secondary operations) | 3 (integrated features) | 40% Reduction |

Note on Machining Time: The 11% increase in spindle time is a critical lesson. True sustainability looks at the total system impact. The extra 5 minutes of machining energy were vastly outweighed by the savings in material extraction, refining, transportation (of 270g less material per part), and the lifetime energy savings of the lighter bicycle. Furthermore, the swarf (metal chips) from our process was clean, unmixed aluminum, increasing its recycling value and yield.

Expert Strategies for Success: Integrating Drilling into Your Sustainable Design

Based on this and similar projects, here is my actionable advice for designers and engineers:

1. Engage with Your Machinist During the Feasibility Stage.

Don’t just send a final CAD file for quote. Bring your sustainability goals and a preliminary model to the table. A seasoned CNC expert will see opportunities for geometric efficiency you might miss. Ask: “How would you machine this to minimize waste?”

2. Design for Mono-Material Assemblies Using Precision Fastening.

A major enemy of recycling is material mixing. We helped a client replace a plastic housing with six different metal inserts by redesigning it as a single aluminum unit. Complex, multi-axis precision drilling allowed us to create all fastener bosses, hinge points, and guides as integral features of the main housing, eliminating contamination and simplifying recycling.

3. Specify Tolerances with Purpose, Not Paranoia.

An ultra-tight tolerance (±0.0005″) often requires multiple machining passes, slower feed rates, and specialized tooling—increasing energy and tool wear. Ask: “What is the functional tolerance for this hole?” A clearance hole for a passive vent does not need the same precision as a bearing seat. Relaxing non-critical tolerances is a direct path to greener manufacturing.

4. Leverage Drilling for Disassembly (DfD).

This is a cutting-edge application. We now design “breakaway” or “shear” features directly into components. For example, a precisely drilled and tapped hole can include a thin, scored web. At end-of-life, a specific torque applied to the fastener shears this web, allowing clean separation. This kind of innovation turns precision drilling services into an enabler of the circular economy.

💡 The Future is in the Hole

The next frontier is data-driven drilling. With IoT-enabled machines, we now collect real-time data on tool wear, spindle load, and energy consumption for every hole we drill. This allows us to build predictive models that further optimize processes for the lowest carbon footprint. The humble drilled hole has become a rich data point in the sustainability story.

In conclusion, moving beyond surface-level eco-friendly gestures requires digging deeper—literally. By treating precision drilling not as a mundane task but as a critical design variable, we can machine products that are inherently less wasteful, more efficient, and truly circular. The path to a greener product isn’t just found in the material datasheet; it’s mapped out in the toolpath of a high-precision drill.