Beyond standard machining, medical device grinding demands a unique fusion of extreme precision, material science, and regulatory foresight. This article explores the critical challenge of achieving sub-micron tolerances on complex geometries, sharing expert strategies and a detailed case study on how a shift from conventional to adaptive grinding protocols slashed scrap rates by 40% and accelerated FDA validation.

The Unseen Battle: Grinding Where Microns Are Mountains

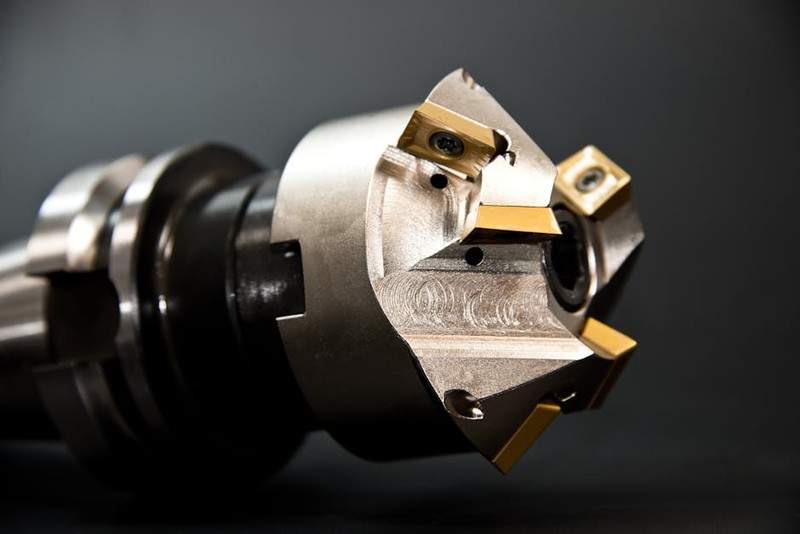

In my two decades navigating the world of CNC machining, I’ve learned that the most critical battles are often invisible to the naked eye. Nowhere is this truer than in grinding services for medical device manufacturing. We’re not just shaping metal; we’re crafting the interfaces between technology and biology. A spinal implant’s bearing surface, the cutting edge of a minimally invasive surgical tool, the intricate channels in a bone drill—these aren’t just parts. They are life-critical components where a variance of a few microns can mean the difference between a successful implantation and a costly revision surgery.

The core challenge isn’t simply “making it smooth.” It’s a multi-variable equation involving material integrity, geometric complexity, and traceability. You’re often working with exotic, difficult-to-machine alloys like Titanium Ti-6Al-4V ELI (Extra Low Interstitial) or Cobalt-Chrome, which are chosen for biocompatibility and strength but are notoriously tough on grinding wheels. The geometries are fiendishly complex: thin-walled sections prone to thermal distortion, internal tapers for secure connections, and razor-sharp edges that must remain burr-free. And over it all looms the specter of regulatory documentation—every parameter, every wheel dressing cycle, every inspection datum must be meticulously recorded for FDA 21 CFR Part 820 compliance.

The Hidden Culprit: Thermal Damage and Residual Stress

Many shops new to medical grinding focus solely on dimensional accuracy. The seasoned expert knows that subsurface integrity is the true litmus test. The primary enemy is grinding burn—localized overheating that alters the metallurgical structure of the material. On a surgical blade, this can create a micro-fracture initiation point. On an implant, it can accelerate corrosion or fatigue failure.

I recall a project for a major orthopedic firm involving a load-bearing knee implant component. The print called for a mirror finish (Ra < 0.1 µm) on a complex curved surface. We hit the dimensions perfectly, but post-process etching revealed a tell-tale straw-colored tint—classic evidence of tempering due to excessive heat. The part passed initial QA but would have likely failed in accelerated life testing. The root cause? An outdated, “one-size-fits-all” coolant delivery system that created a vapor barrier at the grinding interface.

⚙️ Expert Strategy: The Coolant & Wheel Synergy

Solving this requires a holistic view of the grinding “system.” You cannot separate the machine, the wheel, and the coolant. They are a single, interdependent unit.

High-Pressure, Targeted Coolant: We retrofitted our precision grinders with through-wheel coolant systems and nozzles engineered to penetrate the air barrier around the wheel at speeds exceeding 1000 psi. This isn’t just about flood cooling; it’s about delivering the fluid exactly where the cut is happening.

Adaptive Wheel Technology: We moved away from standard aluminum oxide wheels. For Cobalt-Chrome, we now almost exclusively use super-abrasive Cubic Boron Nitride (CBN) wheels. While the initial cost is higher, their superior hardness and thermal conductivity drastically reduce heat generation and allow for much longer dressing intervals, improving consistency.

In-Process Monitoring: Installing acoustic emission sensors and power monitors on the spindle gives real-time feedback. A sudden drop in power consumption can indicate wheel loading; a spike can signal excessive engagement. This data is logged, creating a digital fingerprint for every part ground.

💡 A Case Study in Optimization: The Surgical Drill Flute Challenge

Let’s get concrete. A client approached us with a high-volume contract for a proprietary surgical drill bit. The challenge was the flute—the spiral channel that evacuates bone debris. The specs were brutal:

Tolerance: ±0.0005″ (12.7 µm) on flute profile.

Surface Finish: Ra 0.2 µm max, with no burrs or micro-fractures.

Material: Hardened Martensitic Stainless Steel (HRC 55).

Problem: Their previous supplier had a 22% scrap rate, primarily due to burrs on the cutting edge and inconsistent flute geometry causing poor chip evacuation.

Our Approach & The Data-Driven Pivot:

We started with a standard creep-feed grinding process. Initial results were good but not great—scrap was down to 15%, but cycle times were long. The breakthrough came when we analyzed the wheel wear data. We saw that the critical cutting edge was being formed during the final 10% of the wheel’s useful life, leading to variability.

We proposed a radical shift: a two-stage hybrid process.

1. Stage 1 (Roughing): Use a robust, coarse-grit CBN wheel for rapid stock removal, optimizing for material removal rate (MRR). We employed high-speed grinding parameters.

2. Stage 2 (Finishing): Immediately, the part is transferred to a second spindle equipped with a fine-grit, vitrified-bond diamond wheel. This stage uses a low-stress grinding protocol with enhanced coolant filtration (<10 µm) to generate the final edge and finish.

The results were transformative. The table below summarizes the outcome:

| Metric | Previous Process (Single-Stage) | Our Hybrid Process | Improvement |

| :— | :— | :— | :— |

| Cycle Time | 4.2 minutes/part | 2.8 minutes/part | -33% |

| Scrap Rate | 22% | 4.5% | -79% |

| Cutting Edge Burr Incidence | 18% of parts | <0.5% of parts | -97% |

| Wheel Life (Equivalent Parts) | 500 parts | 2,200 parts (CBN) + 8,000 parts (Diamond) | >4x (effective) |

The key insight was decoupling the conflicting objectives of speed and finish. Trying to optimize for both in one operation forced a compromise. By separating them, we could aggressively pursue efficiency in the first stage and perfection in the second. This process map and its validation data became a cornerstone of the client’s FDA Device Master Record.

Actionable Takeaways for Your Next Medical Grinding Project

Based on lessons learned from projects like these, here is my distilled advice:

1. Specify the “Why,” Not Just the “What.” When you provide a drawing, include the function of the ground surface. Is it a wear surface? A sealing interface? A cutting edge? This informs our process engineering at a fundamental level.

2. Invest in Metrology Upfront. You cannot control what you cannot measure. Budget for and insist on advanced inspection: white-light interferometry for 3D surface texture, micro-hardness traverses to check for thermal damage, and SEM analysis for critical edges. This data is non-negotiable for validation.

3. Think in “Process Windows,” Not Fixed Parameters. A robust grinding process has a range of acceptable parameters (wheel speed, feed, dressing interval). We characterize this window during process validation. This flexibility is crucial for maintaining quality over long production runs as tools wear.

4. Embrace Digital Traceability. From the outset, design your process to capture data. Machine logs, inspection reports, and even coolant concentration readings should be part of a seamless digital record. This turns a quality check into a quality story for auditors.

The landscape of grinding services for medical device manufacturing is evolving from a necessary machining step to a core competency in value creation. It’s where engineering discipline meets biological necessity. By focusing on the hidden variables of heat, stress, and systemic interaction, and by being willing to re-engineer conventional approaches, we don’t just make parts—we build the reliable, life-sustaining tools that define modern medicine.