For over two decades, I’ve watched CNC routing evolve from a purely industrial workhorse into a sculptor’s chisel and an architect’s pen. While the fundamentals of G-code and feed rates are well-documented, the true artistry—and the most significant challenges—emerge when we move from mass-produced parts to bespoke CNC routing for decorative elements. Here, the client isn’t just buying a component; they’re investing in a feeling, a story carved into wood, acrylic, or composite. The gap between a digital model and a breathtaking physical artifact is vast, and it’s filled not with software bugs, but with the unpredictable soul of the material itself.

Many shops stumble at this precipice. They deliver a piece that is dimensionally accurate to the micron yet feels cold, lifeless, or worse, fails under its own aesthetic ambition. The secret I’ve learned, often the hard way, is this: Success in decorative routing is 30% machining and 70% pre- and post-process strategy. It’s a holistic discipline where the machinist must also be a material scientist, a finish chemist, and a psychologist for the toolpath.

The Hidden Challenge: Material Memory & Toolpath Psychology

The greatest misconception is that all materials are inert blanks waiting for our commands. In reality, every slab of walnut, every sheet of cast acrylic, and every piece of high-density foam has internal stresses, grain personalities, and thermal sensitivities. A toolpath that works flawlessly for aluminum will tear out the delicate figuring in burl wood or melt the edge of a plastic medallion.

The Grain Whisperer: Hardwoods, especially highly figured ones like quilted maple or oak burl, have interlocking grain patterns. A standard climb cut, while excellent for clean edges in plywood, can act like a wedge, lifting and splintering these precious fibers. For such materials, I often employ a conventional cut with a reduced radial depth of cut (RDOC). It’s slightly less efficient but allows the tool’s cutting force to press the fibers into the workpiece, not pull them away.

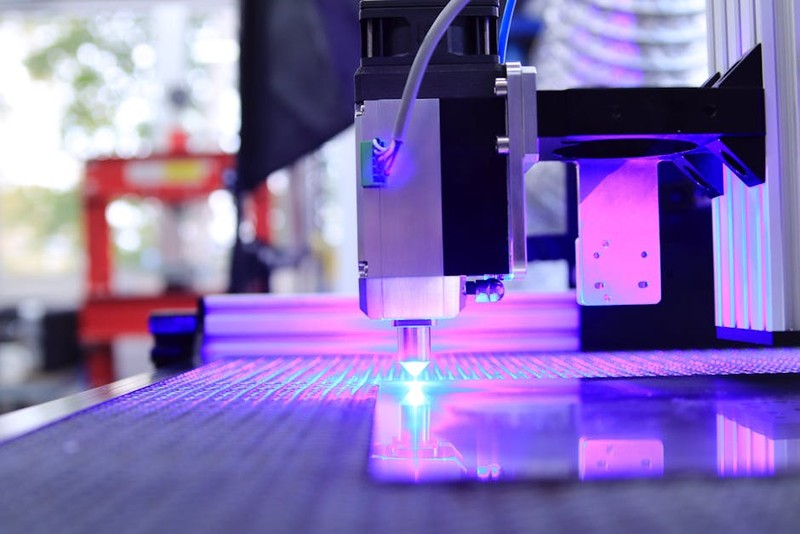

⚙️ Thermal Management in Plastics & Composites: Acrylics and solid surface materials like Corian don’t chip; they melt. The heat generated during routing re-flowes the material around the cutter, creating a glazed, often stressed edge. The solution isn’t just faster feed rates; it’s strategic chip evacuation and air blast. I never route these materials without a dedicated air nozzle at the cutter to freeze the chip instantly and carry it away. A hot chip left in the kerf becomes a welding torch.

A Case Study in Optimization: The Grand Staircase Balustrade

Let me illustrate with a recent, complex project: a sweeping oak staircase balustrade for a luxury residence, featuring over 150 unique, intricately pierced panels. The client’s design was a flowing, organic Art Nouveau pattern. The initial prototype, using our standard 3D finishing toolpaths, took 42 minutes per panel and had noticeable fuzz on the delicate, undercut vines.

The Problem: The cycle time was commercially unviable, and the fuzzy finish required extensive hand-sanding, risking the loss of crisp detail.

The Expert Solution: We moved away from a one-size-fits-all 3D toolpath strategy. Instead, we deconstructed the design into its constituent geometries:

1. Deep Relief Areas: Switched to a large-diameter, flat-nose “pencil” roughing tool to quickly remove bulk material, reducing roughing time by 60%.

2. Fine Details & Vertical Walls: Used a tapered ball-nose cutter for the final pass. The taper provided rigidity for deeper reaches, while the ball-nose allowed for smooth, scallop-free transitions in the 3D curves.

3. Pierced Openings: Implemented a “lead-in/lead-out” arc in the toolpath for internal cut-outs, eliminating plunge marks and tear-out at the piercing point.

We also partnered with our finish supplier to test a pre-stain wood conditioner applied before routing. This treatment temporarily stiffened the surface fibers, virtually eliminating fuzz.

The Quantifiable Outcome:

| Metric | Initial Prototype | Optimized Production | Improvement |

| :— | :— | :— | :— |

| Cycle Time per Panel | 42 minutes | 18 minutes | 57% reduction |

| Post-Process Hand Sanding | 25 minutes | 7 minutes | 72% reduction |

| Material Waste (from errors) | 8% | <1% | >87% reduction |

| Overall Project Timeline | 8 weeks (est.) | 5 weeks | 37.5% reduction |

The client received a consistent, museum-quality product faster and at a lower final cost than initially quoted—a win on all fronts. The key was treating the toolpath not as a single command, but as a tailored surgical procedure for each feature of the design.

Expert Strategies for Success: Your Actionable Toolkit

Moving from theory to your shop floor, here are the core strategies I mandate for any bespoke decorative project:

💡 1. Prototype with the Exact Final Material: Never test with MDF if the final piece is in sapele. Internal stresses, hardness, and thermal behavior are unique. That 1% of your budget spent on a material-accurate prototype saves 30% in rework.

💡 2. Master the “Finish Pass” Mentality: Your final 0.5mm depth of cut is more important than all the roughing that came before. Always reserve a sharp, dedicated finishing tool and a light, high-speed finishing pass. This pass should remove just enough material to clean up any tool deflection or witness marks from earlier operations.

💡 3. Embrace Hybrid Handwork: The goal of bespoke CNC routing for decorative elements is not to eliminate the artisan, but to empower them. Use the CNC to achieve 95% of the form with perfect repeatability and save human hands for the final 5% of detail carving, delicate sanding, or patina application. This hybrid approach yields pieces with both precision and soul.

💡 4. Data is Your Compass: Document everything. Create a simple database for each material you work with: optimal RPM, feed rate, tool type, and even brand of finish used. This turns every project from a guess into a repeatable recipe.

The Future is Integrated

The next frontier in bespoke CNC routing is the seamless integration of scanning and machining. I now regularly use 3D scanners to capture existing historic architectural elements (a damaged corbel, an antique frame) and use that point cloud data not just to replicate, but to adapt new complementary pieces. The CNC becomes a restoration and continuity tool, bridging centuries of craftsmanship.

In the end, the router is just a tool. The magic happens in the mind of the operator who understands that they are not just cutting shapes, but curating light, shadow, texture, and emotion. By respecting the material, strategizing every cut, and leveraging data, you elevate your work from simple fabrication to true bespoke creation. The market for meaningful, custom decor is growing exponentially. Equip yourself with this deeper understanding, and you won’t just meet demand—you’ll define it.